Thinking Through Violent OT Passages

10 hermeneutical principles to help with troubling passages

And David would strike the land and would leave neither man nor woman alive. - 1 Sam 27:9

I have written at length and preached on the violent commands of the Old Testament before, but here I want to just present a set of interpretive principles that I think should be in place whenever we encounter passages that shock us, that may leave us thinking: is God really okay with that?

1. Be Aware of Our Cultural Distance

Consider an analogy. If I took any of you out to a farm, walked you over to a large cow, placed a knife in your hand and told you: “Slit its throat so we can butcher it,” what would you do? My guess is that, unless you grew up on a farm where you killed what you ate, you would be alarmed, maybe even feel it is wrong. Not because killing cattle is necessarily right or wrong, but because most of us have never had to deal with the grisly aspects of getting our hamburgers.

By the grace and mercy of the Lord, most of us reading this do not live in a place where our lives are in jeopardy by a warring tribe, most of us have not seen our daughters and sisters stolen, or our children slaughtered before our eyes. Most of us are not even familiar with serving in the military, fighting in a war, or seeing another human die. Israel was. Israel—and most other nations in the Bronze Age—were familiar with a brutality of fighting to keep their families alive that we struggle to even imagine. This isn’t to justify all acts of violence done back then, not by any means, but it is pointing out that some of our shock and outrage when we read of the violence of the OT simply comes from our total removal of that kind of world.

2. Be Aware of Covenantal Difference

Under the administration of the Old Covenant, war was a common element of Israel’s mission due to the nature of the covenant. Warring with the other nations was inherent to the mission of Israel (see Deut. 20 for example). Why? Because God’s people were identified primarily through their separation from the nations and by their possession of the land of Palestine. But the purpose of the Old Covenant was to set the stage for the New Covenant, where we see the mission of God’s people move to its next stage in redemptive history. Where Israel once was identified by her separation from the nations, the Church is now commanded to go unto all the nations and make disciples of them (Matt 28:18-20). In many ways, the Great Commission is the exact reversal of the Canaanite conquest. Where Israel was identified by possessing a specific land-mass in the Middle-East, the Church is identified by possessing a better land, the New Creation, and so remain as exiles and sojourners spread throughout all nations. The Church doesn’t fight against flesh and blood to defend an earthly kingdom of God, but wields the sword of the Spirit (Eph 6:10-17) in fighting against spiritual powers in its conquest for heavenly kingdom. Where Old Covenant Israel practiced capital punishment for high-handed sins, the Church practices church discipline (1 Cor 5:13).

As the story of the Bible unfolds, the move is away from God’s kingdom using violence to expand its borders. We follow Jesus’ model of suffering, sacrifice, and love of enemy. Tertullian, commenting on Jesus’ rebuke of Peter for picking up the sword to defend Him (Luke 22:50-51), said: “In disarming Peter, Christ disarmed all Christians.” Now, under the New Covenant, the mission of God is not extended by physical force, coercion, or extermination of enemies—but through persuasion, conversion, suffering, and love of enemies. Again, this doesn’t answer the questions about the violence we find in the Old Testament, but it does also show us that the story of redemption doesn’t lead us towards violence, but away from it. I don’t believe this requires pacifism, but if Christians seek to justify violence by appealing to OT conquest narratives, they are cutting against, not with, the grain of Scripture. The whole current of progressive revelation is flowing towards the day where all war, bloodshed, and violence will be done away with, forever (cf. Isa 2:4).

3. Be Aware of the Reality of Death

No one dies of natural causes. Everyone dies at some point because God has allotted to us all a certain number of days (Ps 39:4). “The LORD kills and brings to life,” (1 Sam 2:6). God takes life because He is the author of life. True, death is a by-product of sin (Gen 2:17), the right consequence for violating God’s Law, but God is the one who administers such consequence—even as God works to defeat and undo it (Heb 2:14-15; 1 Cor 15:26).

Now, when we read of moments in the Bible where God seems to have a much more active hand in the death of someone, like the earth opening up to swallow sinners (Num 16) or a people being devoted to destruction (1 Sam 15:1-3), we are not witnessing God doing something strange by actively dealing out death. We are simply seeing an extraordinary display of what He normally does. Whether one dies at a ripe old age in a hospital bed or in brutal hand-to-hand combat, God kills us all—Christian and non-Christian—at some point.

4. Be Aware of the Reality of Judgment

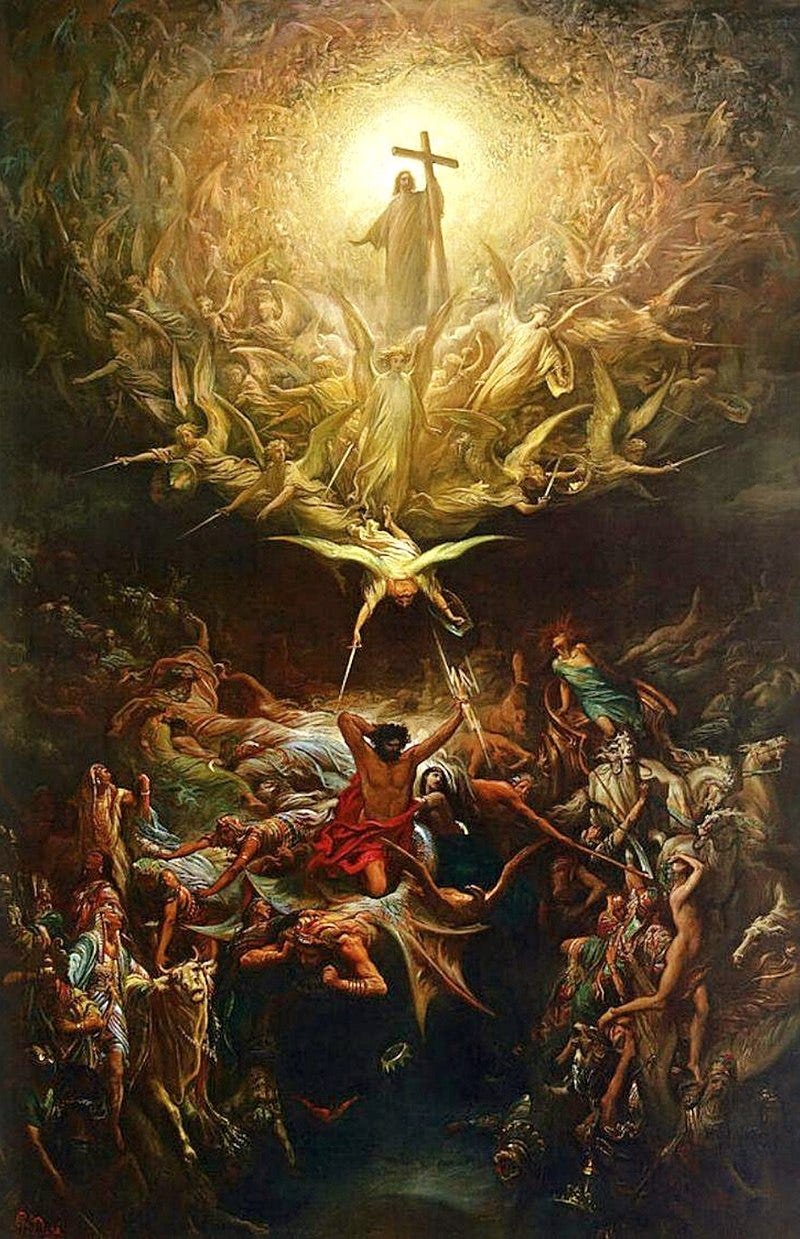

God will judge all persons. When I said in point 2 that the trajectory of the Bible is away from violence, that is only partially true. There will be a violent, calamitous, final war that will result in the complete destruction of God’s enemies (Rev 19:11-21). As Meredith Kline writes, what we see in the Canaanite conquest is a picture of the final judgment intruding back into history. At the Last Day, all persons will appear before the throne of God and receive the exact fair reward or curse for their conduct in life. “He will render to each one according to his works: to those who by patience in well-doing seek for glory and honor and immortality, he will give eternal life; but for those who are self-seeking and do not obey the truth, but obey unrighteousness, there will be wrath and fury. There will be tribulation and distress for every human being who does evil, the Jew first and also the Greek, but glory and honor and peace for everyone who does good, the Jew first and also the Greek. For God shows no partiality,” (Rom 2:6-11).

You will either die in your sins, or die in your sinless Savior who died for your sins. When we see God pour out wrath on a nation or person in the Bible, it may strike us as bizarre and contrary to God’s loving character—but if our conception of God’s love excludes His justice, then we have a malformed understanding of love (see point ten below). In fact, we will actually find the love of God less amazing if we see His wrath as misplaced. A king pardons two lawbreakers in his land. Both of them deserve death, yet both are spared. One knew his law-breaking deserved death, the other assumed that the king didn’t have it in him. Which one of them loves the king more?

Also, consider this: we tend to be scandalized by the presence of judgment; most of the authors of the Bible, on the other hand, tend to be scandalized by the delay of judgment. The martyrs before the throne of God cry out to Him, “How long before you will judge and avenge our blood?” (Rev 6:10). People in the Bible are tempted to question God’s goodness because He seems so slow to judge, not the other way around. When judgment is poured out, the saints in heaven rejoice: “Hallelujah! Salvation and glory and power belong to our God, for his judgments are true and just; for he has judged the great prostitute who corrupted the earth with her immorality, and has avenged on her the blood of his servants. Once more they cried out, “Hallelujah! The smoke from her goes up forever and ever,” (Rev 19:1-3).

5. Be Aware of Hyperbolic Language

I have written at length on this issue here. Not every command to destroy “man-woman-child” is necessarily hyperbolic, but many of them are. This isn’t questioning the inerrancy of God’s Word or the reliability of it, but is stating that a straightforward reading of much of the language in the war narratives obviously point to the fact that the authors are intentionally using hyperbolic language to communicate a decisive victory, not genocide. Think of describing a sports victory as a “massacre” today.

6. Be Aware of the Nature of the Canaanite Conquest

I have written about this at length here. In sum, the Canaanite conquest was not genocide. It was never based on ethnicity. God supernaturally sent angelic messengers ahead of Israel to warn the inhabitants of their need to flee. Military outposts, not civilian centers were targeted. Canaanite individuals, like Rahab, who turned in faith to Yahweh were spared.

7. Be Aware of What You Are Reading

The authors of the Bible assume that you are a mature reader. Just because the Bible describes something does not mean that it is prescribing it. There are many instances where the Bible describes something that it explicitly condemns elsewhere. For example, Lot’s drunken sex with his daughters is described in Genesis 19 without any explicit condemnation by the author. David’s taking of a second and third wife in 1 Samuel 25 is reported without any word of criticism. Does this mean that God endorses these acts? Of course not. It means that the authors of these stories are sophisticated storytellers that assume they do not need to interrupt the narrative every time to lean over and say, “Just so you know, these things are bad, okay?” God’s moral standards have been clearly revealed in His Law. And even when someone who seems like a hero—like, David—does something that contradicts God’s Law, we know that David is wrong. So, when we are reading a story in the Bible that puzzles us in its moral complexity, we should stop and ask ourselves: is this just describing something, or is God prescribing something? If it is prescribing something, then I would point you to points all the other points in this article. If it is just describing something, then hold up the description in light of the more clear moral commands of God’s law to determine whether or not this is something being endorsed or not.

At times, it can admittedly be hard to discern. For instance, when David attacks the Geshurites, Girzites, and Amalekites in 1 Samuel 27, he leaves “neither man nor woman alive” (1 Sam 27:9). Now, we are told that David does this, “for these were the inhabitants of the land from of old.” This could mean that the author is showing us that David’s raids are legitimate extensions of the Canaanite conquest, since these are inhabitants that God had promised to push out of the land and devote to destruction (see Josh 13:2, 16:10, and 1 Sam 15:1-3). But, we are also not told that David has been instructed by Yahweh to do so in the same way Saul was (1 Sam 15:1-3), so he seems to take matters into his own hands (a very negative theme in 1 Samuel). Further, we are told that David takes all the livestock of the defeated people, and then lies about what he has been doing (1 Sam 27:9-10). In fact, we are even told that the reason why David leaves no man or woman alive is so they won’t bring back news to Gath to inform Achish (1 Sam 27:11). This inclines many interpreters to see that David’s raids here are not a morally sanctioned act, but sin.

8. Be Aware of God’s Moral Standards

When Abraham hears that God intends to destroy Sodom and Gomorrah, he is alarmed. “Will you indeed sweep away the righteous with the wicked? Suppose there are fifty righteous within the city. Will you then sweep away the place and not spare it for the fifty righteous who are in it? Far be it from you to do such a thing, to put the righteous to death with the wicked, so that the righteous fare as the wicked! Far be that from you! Shall not the Judge of all the earth do what is just?” (Gen 18:23-25). Abraham knows enough about the character of God to realize that for God to treat the righteous like the wicked would compromise God’s character, God’s justice. And he goes so far as to censor God! Far be it from you to do such a thing. Amazingly, God doesn’t respond to Abraham with “Who are you, O man, to answer back to God?” (Rom 9:20). He is incredibly patient with Abraham (Gen 18:26ff). This shows us that there is a way in which we can argue with God, so to speak, that God welcomes. How do you do that? You argue from God’s standards, not your own. There is a way in which we can respond to God with a hardened skepticism that requires God to conform to our own definitions of right and wrong, that is arrogantly confident that we understand everything and so have the right to scrutinize God—which is really another way of saying we want to be God. But there is a way we can humbly say: God, I know you are good, but I am struggling to understand how *this* is good. Help me.

For Abraham, the problem was that he misunderstood the situation. He assumed that there were righteous people living in Sodom and Gomorrah, when really there was only Lot. Abraham thought God was going to sweep away the righteous with the wicked, but He wasn’t. When we are reading something in the Bible that seems to contradict what we clearly know to be true about God, it may be because we have misunderstood the situation. But no matter what, we can be confident that the Judge of all the earth will always do what is just. The problem is never in Him, but in our own limited understanding.

9. Be Aware of God’s Heart

“Have I any pleasure in the death of the wicked, declares the Lord GOD, and not rather that he should turn from his way and live?” (Ez 18:23)

“For I have no pleasure in the death of anyone, declares the Lord GOD; so turn, and live,” (Ez 18:32)

“As I live, declares the Lord GOD, I have no pleasure in the death of the wicked, but that the wicked turn from his way and live; turn back, turn back from your evil ways, for why will you die, O house of Israel?” (Ez 33:11)

“For the Lord will not cast off forever, but, though he cause grief, he will have compassion according to the abundance of his steadfast love; for he does not afflict from his heart or grieve the children of men,” (Lam 3:31-33).

“God our Savior…desires all people to be saved and to come to the knowledge of the truth,” (1 Tim 2:4)

“The Lord is not slow to fulfill his promise as some count slowness, but is patient toward you, not wishing that any should perish, but that all should reach repentance,” (2 Pet 3:9)

Catch the theme, here? God does not “afflict from his heart.” Judgment does not flow from God’s heart the way mercy does. The Bible speaks of God needing to be provoked to anger, but not once does it say He must be provoked to love—anger requires provocation, love flows freely from Him. He does not delight in judgment the way “he delights in steadfast love,” (Micah 7:18). Judgement is his “strange work” (Isa 28:21), while showing mercy and steadfast love is something God does “with his whole heart, and with his whole soul,” (Jer 32:41).

This isn’t cherry picking verses to downplay the more gruesome bits. This is following Scripture’s own lopsided emphasis it puts on steadfast love over judgment. Even in the most classic disclosure of God in the OT, Exodus 34:6-7, you see this lopsided emphasis where God’s steadfast love and mercy are extended “to the thousandth generation”, while the judgment of iniquity extends only “to the third and fourth generation.”

10. Be Aware of God’s Judgment as a Display of God’s Love

The Bible tells us “God is love,” (1 John 4:8, 16). Nowhere does the Bible say, “God is wrath.” But, lest I confuse you, that doesn’t mean that God isn’t wrathful. It means that wrath doesn’t define Him essentially the way love does. But also, paradoxically, that means God’s wrath, therefore, must be a display of God’s love. While everything above is true, David also tells us, “God is a righteous judge, and a God who feels indignation every day,” (Ps 7:11). Why? Because God is love. Consider what Yale theologian, Miroslav Volf, writes:

I used to think that wrath was unworthy of God. Isn’t God love? Shouldn’t divine love be beyond wrath? God is love, and God loves every person and every creature. That’s exactly why God is wrathful against some of them. My last resistance to the idea of God’s wrath was a casualty of the war in the former Yugoslavia, the region from which I come. According to some estimates, 200,000 people were killed and over 3,000,000 were displaced. My villages and cities were destroyed, my people shelled day in and day out, some of them brutalized beyond imagination, and I could not imagine God not being angry. Or think of Rwanda in the last decade of the past century, where 800,000 people were hacked to death in one hundred days! How did God react to the carnage? By doting on the perpetrators in a grandfatherly fashion? By refusing to condemn the bloodbath but instead affirming the perpetrators’ basic goodness? Wasn’t God fiercely angry with them?

Though I used to complain about the indecency of the idea of God’s wrath, I came to think that I would have to rebel against a God who wasn’t wrathful at the sight of the world’s evil. God isn’t wrathful in spite of being love. God is wrathful because God is love." (Volf, Free of Charge, p. 138-39)

Of course, this is displayed supremely in the cross of Jesus Christ, where love and wrath mingle most potently. God’s love for the world did not come at the expense of wrath, but in the righteous dispensing of wrath upon sin—only, sin that had been absorbed into our sinless Savior’s flesh nailed to the cross. So now, there is a way of escape for sinners like you and myself from the wrath we deserve. You can die in your sins and face the indignation of a Righteous Judge. Or you can die in your Savior, the Righteous Sacrifice.

And can it be that I should gain

An int'rest in the Savior's blood?

Died He for me, who caused His pain?

For me, who Him to death pursued?

Amazing love! how can it be

That Thou, my God, should die for me?