1 Corinthians 11:2-16 is complex for many reasons. One of the most bedeviling difficulties for interpreters is discerning what Paul precisely means by “covering” in this section. Generally, there are two possible interpretations, each with serious merit. I will be preaching a sermon on this passage soon, but have found a number of complex issues to wade through that wouldn’t be helpful to include in a sermon, so I will provide them here, and will concern the sermon with what application of this passage actually means.

Hair

It is possible that the “head covering” Paul refers to refers to long hair either being done up in a bun or braid on top of your head (head covered), or refers to your hair being let down loosely. In support of this interpretation, Paul never actually uses the typical term for a veil (kaluma; see 2 Cor 3:13) in this entire section. The one place he uses an actual term for “covering” is when he uses a very rare term (peribalaion), but there Paul explicitly says that a woman is given long hair as a covering. When he speaks of what is on top of a man’s head that is shameful he speaks rather obliquely. If we were to translate 1 Cor 11:4 very literally it would say: “Every man who prays or prophesies having something coming down from his head (kata kephalēs echōn) dishonors his head.” Thus what is coming down from his head—hair or a veil of some sorts—is up for debate. But there are good reasons for seeing it as referring to hair, not a head covering.

First, similar language that Paul uses in this section is used in the Greek translation of the Old Testament (LXX)—which would have been Paul’s Bible—to refer to hair, not a head covering. Numbers 5:18, speaks of a woman being charged for adultery and states that she must “let down her hair” (apokalupsei tēn kephalēn) which sounds very similar to Paul’s language in 11:5 (akatakaluptō tē kephalē). Further, “the same Greek word that describes the practice of the Corinthian women in 11:5 (akatakaluptos) is used in Leviticus 13:45 about a leper’s hair, which is to hang unbound,” (Schreiner, TNTC: 1 Corinthians).

Second, this would explain why Paul begins to speak about hair in verses 14-15, with the shame of men wearing long hair and the glory of women’s long hair (and Paul’s comments regarding women’s hair in vs. 5-6). In particular verse 15 says of a woman’s long hair: “…her hair is given to her for a covering,” (1 Cor 11:15). In fact, the word “for” in this verse (anti) is usually used for substitution, so a more natural translation of verse 15 would read: “…her hair is given to her instead of a covering.” Thus, it seems the woman’s hair is her covering, and no veil is required.

Third, Paul assumes that men having their head covered in worship is obviously dishonorable. But, this was not dishonorable in Greco-Roman culture. When Roman men would attend a temple to offer sacrifices, they would usually pull part of their toga over their head (known as: capite velato) as a sign of reverence and piety.

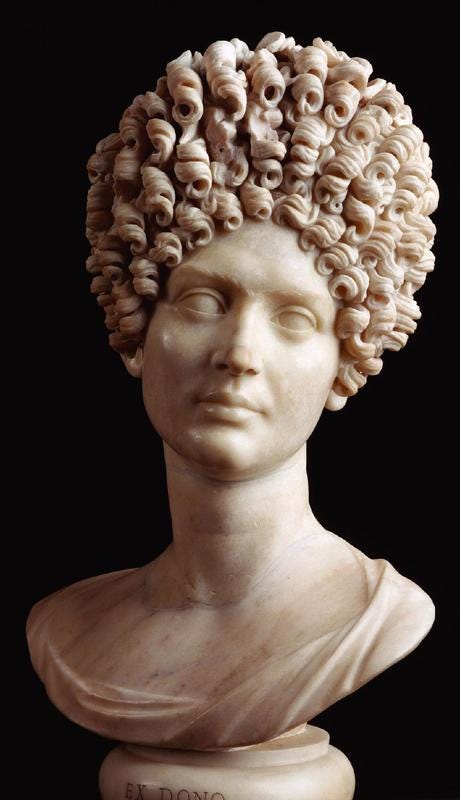

Thus, men wearing a covering on their head in worship would not be considered shameful in Corinthian culture, but the opposite. Thus, it seems more likely that the shameful covering Paul refers to here is to men wearing long, effeminate hair, possibly braided and done up like women. Also, interpreting a woman’s head being “uncovered” as having loose, unbound hair would fit the shame Paul assumes it brings (1 Cor 11:5-6). Nearly every portrait, fresco, and sculpture we have today of Roman women depict their hair being done up with “a clasp, hairnet, headband, ribbon, or some other utensil,” (Philip B. Payne, Man and Woman, One in Christ, p. 150). Significantly, in very few of these representations do we see women wearing a shawl or head covering. The only women who wore their hair down loose in public were prostitutes (hetaira) and women worshipping in the cult of Dionysus, which was associated with sexual promiscuity. Paul claims that if a woman will not wear a head covering, she should have her head shaved—a common punishment of adultery in antiquity.

Fourth, the ESV translates 1 Cor 11:10 as, “That is why a wife ought to have a symbol of authority on her head…” But the verse literally says: “That is why a wife ought to have authority on her head…” Thus, whether the authority refers to a symbolic object on her head that represents an authority she submits to (a veil, or even a certain hairstyle) or whether she possesses authority over her own head must be determined by the wider context. Admittedly, the context of the section seems to cut against the idea of translating it as referring to the woman’s authority over her own head, which is why most translations have decided that the authority spoken of is a symbol of authority (ESV, CSB, NKJV, NET, NASB, ASV, NLT, NRSV; exception: NIV). Nevertheless, the symbol could be either a hair style or a head covering.

So, in this interpretation the man wearing a “head covering” would be a man with long hair wearing a hair-style that is clearly effeminate and possibly a sign of telegraphing homosexual orientation (more specifically, the passive partner in a homosexual act, see 1 Cor 6:9, malakoi). Further, the women would be bucking all norms and decorum by appearing immodestly (according to those customs) by letting their hair freely flow down their back.

Head Covering

While the arguments for interpreting the head covering as a certain hair style are considerable and could be correct, it is more likely that Paul refers to some kind of head covering.

First, while the phrase that Paul uses to describe the man having his head covered in 1 Cor 11:4 is ambiguous (kata kephalēs echōn), the exact same phrase is used in Esther 6:12 (LXX): “But Haman hurried to his house, mourning and with his head covered (kata kephalēs echōn).” In the context of that verse, we see clearly that Haman is not being described as having long hair, but hiding his head in shame. The “thing coming down from his head” obviously means his robe being draped over his head.

Second, while the typical word for “veil” is not used (kaluma) here, all of the words used to describe the woman’s head being uncovered (akatakaluptō) or covered (katakaluptō) all come from the same root word that kaluma comes from: kaluptō, which means “to be hidden, or veiled.”

Third, while Numbers 5:18 and Leviticus 13:45 use cognates of kalupto to refer to hair being unbound, there is also ample evidence of cognates of kaluptō to frequently describe a veil of some kind, especially when used with “head.” For instance, as David flees Jerusalem in shame, we are told: “David went up the ascent of the Mount of Olives, weeping as he went, barefoot and with his head covered (epikaluptō). And all the people who were with him covered (epikaluptō) their heads, and they went up, weeping as they went,” (2 Sam 15:30). The seraphim in Isaiah hold up their wings to cover (katakaluptō) their face and feet (Isa 6:2). Judah confuses Tamar for a prostitute “for she had covered (katakaluptō) her face” with a “veil” (Gen 38:14-15). The desperate farmers of Judah “are ashamed; they cover (epikaluptō) their heads,” (Jer 19:4).

Fourth, Philo, the Jewish philosopher who lived from 20 BC-50 AD, uses the same words Paul does in 1 Corinthians 11:5, head uncovered (akatakalyptō tē kephalē), and it is clear that Philo speaks of a head-covering being removed because the priest had just removed her headdress (Spec. Laws, 3.60 and 3.56; cf. also Alleg. Interp. 2.29).

Fifth, there are a number of portraits which show women with their heads covered.

Plutarch wrote, ‘it is more usual for women to go forth in public with their heads covered and men with their heads uncovered’ (Quaest. rom. 267A). Historian Bruce Winter argues persuasively in After Paul Left Corinth and Roman Wives, Roman Widows that married women in Roman culture wore a veil in public—pulling up a part of their robe over the back half of their head—to telegraph their status as a chaste, married woman. The reason that few are displayed in portraits or sculptures is because they likely would have been viewed as unnecessary. The purpose of the veil was to communicate to the community that you were a married woman, but the veil would often be removed once you were in your own home (since the social necessity now no longer presented itself). Prior to the reign of Caesar Augustus, there was, however, a revolt against the practice of head coverings by Roman women. The “New Wives” were wives who grew frustrated with the sexual double-standards of Roman society, where it was assumed that husbands would have affairs, but women were severely punished for doing so. The symbol of their chaste commitment (the veil) was rejected by these “New Wives” who began to embrace the same sexual liberty their husbands enjoyed. This led Augustus to enforce strict marital laws (leges Juliae) that penalized adultery. Perhaps this is the social background that gives Paul such concern about women failing to wear the head covering. By doing so, they give the appearance that they are rejecting their marital vows of chastity! Winter writes:

By deliberately removing her veil while playing a significant role of praying and prophesying in the activities of Christian worship, the Christian wife was knowingly flouting the Roman legal convention that epitomised marriage. It would have been self-evident to the Corinthians that in so doing she was sending a particular signal to those gathered. (Roman Wives, p. 96)

Sixth, while Roman men did wear a head covering when going in to offer sacrifices in pagan temples, this does not make Paul’s condemnation of men wearing head coverings any less meaningful. Paul clearly does not want the church to confuse its corporate worship with the rituals of pagan worship (cf. 1 Cor 10:20-21). Given the analogy he draws from gender appropriate hairstyle in vs 14-15, perhaps the men were donning head coverings that were being confused as a blurring of gender lines in some sense, maybe out of a confusion over Paul’s teaching that in Christ “there is no male or female” (Gal 3:28). Or perhaps the issue stems from how others would have interpreted the male head covering. Only men who were socially elite wore the toga, and only certain high-class individuals would cover their heads with it while offering sacrifice. Perhaps the Corinthian men who assume the same practice in the church are creating divisions by flaunting their social status, and so creating divisions, and thus dishonoring their head, Christ (cf. 1 Cor 11:22).

Seventh, if the head covering interpretation is correct, then what are we to make of Paul’s sudden transition to describing hair styles in vs. 14-15? Doesn’t Paul say that the women are given long hair “instead of” a covering? The preposition anti used in vs. 15 is most frequently used to for substitution. However, replacement isn’t the only use of anti; it can also be used for equivalence. BDAG explains that it is used for “various types of correspondence ranging from replacement to equivalence.” The New International Dictionary of New Testament Theology and Exegesis explains:

ἀντί is freq. used of substitution, exchange, or the like, i.e., when an entity or act that is distinguishable from another is set/given/taken/done “instead of, in place of” the other…But there is only a small conceptual distance between treating two entities as exchangeable and treating them as equivalent, so that the prep. can be transl. “like, as, for.”

So, when feminist scholar Lucy Peppiat argues that if we just “let the Greek speak for itself” we will obviously translate anti as “instead of”, she is being somewhat disingenuous. When there is a semantic range of meaning for a word we must translate it according to what the context requires. And the context shows us that Paul is making an equivalence here between long hair and the head covering. The NIDNTTE, in its entry on ἀντί, cites its use in 1 Cor 11:15:

Paul’s point is not precisely that veils are superfluous for women on the ground that nature has given them “hair in place of a covering.” Rather, he is arguing analogically: from the general fact that “hair has been given to serve as a covering” he infers that the long hair of a woman shows the appropriateness of her being covered when she prays or prophesies in the Christian assembly.

Tom Schreiner concludes:

To sum up: the custom recommended here probably denotes a veil or a covering of some kind. For a woman not to wear such a covering in public in the first century may have had sexual connotations, suggesting the woman was sexually available. For instance, Lucius says in the work by Apuleius about the hair of women, ‘my exclusive concern has always been with a person’s head and hair, to examine it intently first in public and enjoy it later at home’ (Metam. 2:8), and the context makes it clear that there are sexual connotations here (Metam. 2:8–9). In any case, the main point of the text is clear: women are to adorn themselves in a certain way,” (Schreiner, TNTC: 1 Corinthians).

In Conclusion

The evidence for the “head covering” referring to hair styles is admittedly strong. In fact, it is possible that both meanings are intended. Perhaps a woman having her hair bound up with a head covering of some sorts is what Paul intends. Nevertheless, the evidence seems to tilt towards understanding a head covering for women being commended by Paul.

What this means for today as we seek to transition away from the Corinthian culture to our own is another layer of difficulty. All the nuances needed for taking the timeless, universal theology that undergirds Paul’s argument and applying it to our own time is outside the purview of this article, but simple principles could be deduced:

Women and men should not attempt to blur gender lines in their dress or mannerisms. They should adopt culturally appropriate dress that telegraphs their acceptance of their identity as male or female.

Wives should adopt culturally common customs that display their submission to their husband and modest dress. To this day, a woman’s hair is clearly a sign of her feminine beauty. Women should consider how to use their distinctly feminine beauty in a way that does not lead to immodesty.

In corporate worship, we should not dress or act in such a way that creates divisions in the church between rich and poor, or any other class.