The words of the Preacher, the son of David, king in Jerusalem. - Eccl 1:1

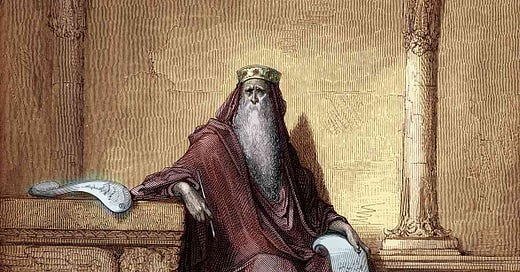

The traditional understanding is that Qoheleth (“the Preacher” ESV, 1:1) is Solomon, writing at an old age, after he repents from his apostasy (see 1 Kings 11).

That being said, there are a number of strong arguments in favor of someone other than Solomon authoring the book. I’ll state the most obvious, less technical arguments first.

Not Solomon

Solomon is never identified as the author of the book. In the other wisdom books traditionally understood to come from Solomon (Proverbs and Song of Solomon), both of those bear his name as the author (Prov 1:1, 10:1; Song 1:1). All we are told is that Qoheleth is a “son of David, king in Jerusalem” (1:1). Solomon would certainly fit this description, but so would many other kings from David’s line.

Certain passages seem to assume that there were numerous other kings who reigned in Jerusalem prior to the author, for example, “I said in my heart, “I have acquired great wisdom, surpassing all who were over Jerusalem before me, and my heart has had great experience of wisdom and knowledge,” (1:16, see also 2:7, 9). But, of course, there was only one Israelite king who reigned over Jerusalem prior to Solomon: David. Saul never conquered Jerusalem, only David did (2 Sam 5). It would seem an odd statement for Solomon to make if “all who were over Jerusalem before me” only meant his father.

The author speaks in the past tense in 1:12 about his reign, “I, the Teacher, was king over Israel in Jerusalem,” (NIV). This sounds like someone reflecting back on their time as king, not someone currently ruling.

The introduction in 1:1, and the epilogue in 12:9-14, reveals that there must be some editor (usually called a “frame-narrator”) since Qoheleth is referred to in the third-person (see also 7:27). Even if Qoheleth is the historic Solomon, then the there must be someone else who is at the very least collecting Solomon’s teachings and arranging them, and then writing out the introduction and conclusion to the book. This is like realizing that John, not Jesus, was the author of John’s Gospel, despite Jesus being the primary speaker and subject in the book.

Lastly, the form of Hebrew used in Ecclesiastes bears a resemblance to a time period much later than that of the historic Solomon. The verbiage and style more closely resembles that of the Mishnah, which was written around the third century BC. This would be a little like reading something today that was written in our contemporary, modern English, but claiming that Shakespeare wrote it.

There are more arguments, but these represent what seem to me to be the most persuasive to see the author as someone other than Solomon.

Solomon

On the other hand, there are many good responses to all of those claims that could defend the historic view of Solomonic authorship.

While we are never told that Solomon is the author explicitly in the book, the book clearly sounds like it is from Solomon. What other king would fit the superlative descriptions of wisdom and wealth we find in 1:12-2:11 (esp. 1:16) or 12:9? Further, 1:12 tells us that Qoheleth “was king over Israel in Jerusalem.” Technically, this could only refer to either David or Solomon, since these are the only two kings who ruled a unified Israel from Jerusalem. After Solomon’s reign, the kingdom splits in two (see 1 Kings 12ff).

The passages that appear to claim that there were numerous other kings ruling in Jerusalem prior to the author on first glance make it appear that this must be someone much later than Solomon. But 1:16 simply says, “I have increased in wisdom more than anyone who has ruled over Jerusalem before me.” This isn’t limited specifically to Israelite kings, but to any king who ruled over Jerusalem, including those prior to David’s conquest of Jerusalem (see Gen 14:18, Josh 10:1 for example).

The verb in 1:12 was, as in “I the preacher was king” (NIV), does not necessarily convey past-tense only, but can refer to something that took place in the past, but has ongoing effects (hence the ESV’s translation “I the preacher have been king.” The verb is in the perfective tense, which “can have the force “have been and still is,” (Tremper Longman III, NICOT: Ecclesiastes).

The existence of a frame-narrator does not negate Solomonic authorship. One option is that Solomon is merely speaking of himself in the third-person in 1:1 and 12:9-14. A more likely scenario is that a later editor(s) collected these teachings as they were passed down from Solomon, much like later editors compiled and arranged the books of Proverbs or Psalms into their final form. So, a scribe or school of scribes could have copied down Solomon’s teaching, while adding the introduction (1:1) and epilogue (12:9-14).

The late Hebrew language is particularly problematic for dating the book back to the time of Solomon, but this could be explained by post-exilic scribes simply modernizing the language as they are copying the book down, much in the same way that our English Bibles today represent a diction and style of language of our own time. Were someone today to pick up a copy of any modern translation of the Bible and then conclude that the authors of this book must originate from at least the 20th century AD, we could respond: No, the original book is much, much older. This is just a modernized translation.

In Sum

There are more arguments that each side could marshal, but in the end the authorship of the book does not matter terribly. The inspiration and authority of the book does not rest on Solomonic authorship—there are many books in the Old Testament in particular that we uncertain of who the author was. The fact is that the Preacher of Ecclesiastes is certainly meant to invoke the figure of Solomon as you read his unsettling message. I am persuaded that the book originates with the historic Solomon, but has been edited into its final form as we read it today.