Voting in 2024 (Pt. 1)

Casting, Compromise, Conscience

Casting Votes

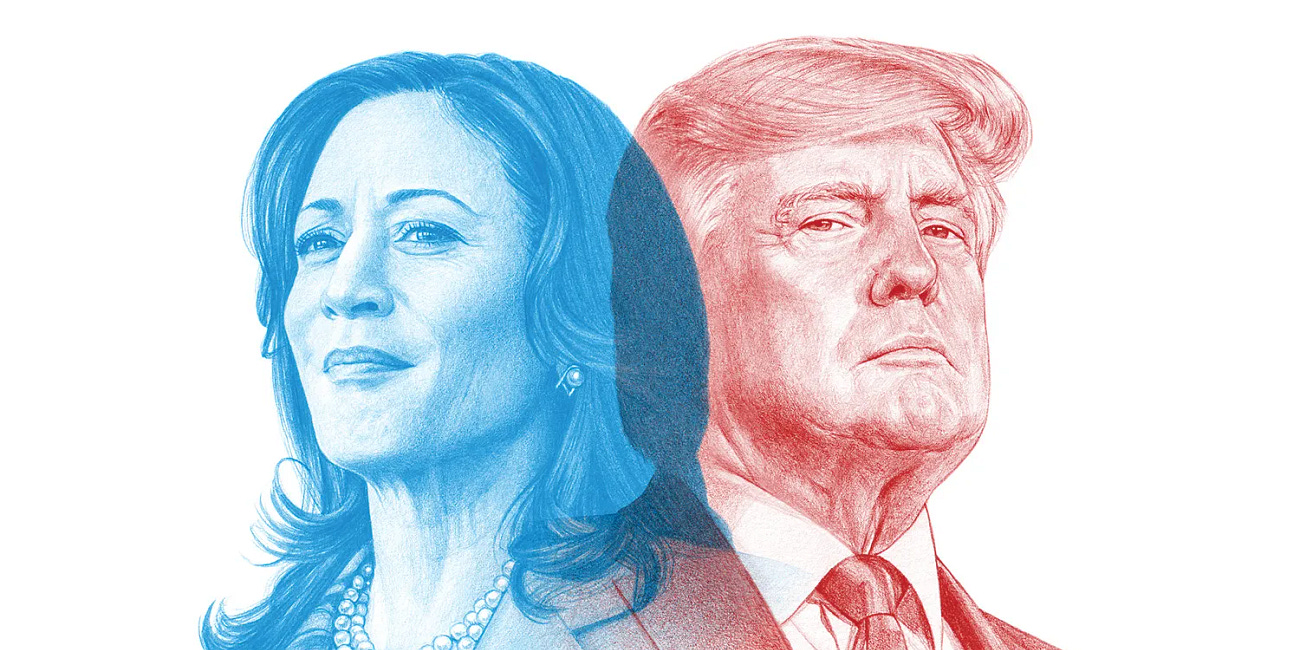

You may hate that we have a two-party system in America. You may despise the two candidates—most Americans do. But the reality is that come November, either the Republican candidate (Trump) or the Democratic candidate (Harris) will be made president. George Washington is the only president who became (and remained) president with no party affiliation. Third-party candidates, apart from never-before-seen circumstances, will not win.

This does not mean, however, that a vote for a third-party candidate is a waste. Partisans will tell you that a vote for a third-party candidate is really a vote for the opposing party—but that argument works in both directions, (a voter’s non-vote for Trump is also a non-vote for Harris). After elections, both parties do extensive research on who they lost votes to—including third-party platforms. Thus, there is a tactical role that voting third-party plays. If enough voters coalesced around a particular platform, the party may adopt some of those policies and positions to their future platform (consider the way Bernie Sanders’ Democratic Socialism influenced the Democratic party in 2016 and 2020 as an example of this). It is not only a protest vote (“I cannot vote for either”), but a longterm attempt to shape future elections (“I hope next time around, I can.”).

Nevertheless, if you vote for a third-party candidate, or even if you do not vote, the part you play in selecting either candidate—Trump or Harris—is inevitable. You cannot escape it. You may feel conscience-bound to not vote for either candidate—which we will come to in a minute—but since our nation decides its leader based on the vote of the people, your absence from the process is itself a decision that affects the outcome. If one-hundred people on a desert island are trying to elect who their leader will be, each person who refuses to take part in the process shrinks the pool of voters, and thus skews the vote. If they all did participate, the majority may choose a different candidate. In a democracy, there is simply no way to escape this.1

So, the person who wants to wash their hands clean and take no part in voting, nevertheless, still bears tangential, even if minute, influence on the outcome. Which leads to the next point.

Compromise

Because there is no way to escape the political process in a democracy, this means that all of us will have to accept an outcome that is not ideal, to make compromises. What do I mean?

Until “Jesus Christ” is on the ballot, none of us will be able to vote for an individual that we have no reservations about. Don Carson explains:

If we live in a democracy…inevitably that means that we are called, in some way, in some measure, to compromise. I have lived in and voted in three different countries. I have yet to vote for somebody concerning whom I had no questions whatsoever of the choices they would make. I suppose that makes me a rotten compromiser. Or does it mean instead that you make choices regarding what are, in your view, the least objectionable courses that are likely to ensue if person A as opposed to person B exercises authority?

Further—and this my come as a surprise to you—but politicians have been known to not be entirely honest about their positions on things. They have even been known to change their mind. Donald Trump, for instance, in 2016 said that he was so fiercely pro-life that he supported punishing women who had abortions (a position he quickly walked away from). But in August of this year, when asked how he would be voting on an abortion referendum in his home state of Florida, Trump insinuated that abortion should be expanded (a position he quickly walked away from).2 Kamala Harris, likewise, has changed her position on immigration, fracking, and defunding the police, among others.

So, you may believe that you can vote for a particular candidate because of their strong commitments…only to find that when push comes to shove, they don’t follow through on their promises. For better or worse, the democratic process means that politicians are always checking which way the wind is blowing so that they can win the next election. Which means that there is always the risk, even on the matters we feel we are not compromising on, that the candidate will not give us the outcome we were promised.

Which means that all of us, even those voting third-party3, will have to make compromises this November.

“How can I avoid compromise?” is the wrong question.

“What am I willing and unwilling to compromise on?” is the right one.

Which brings us to the next point.

Conscience

You conscience is not infallible. Scripture is abundantly clear that it can be seared (1 Tim 4:2), overly sensitive (1 Cor 8:7), or misled (Rom 14). Your conscience is not the north star—God’s Word is. But your conscience is the internal alarm system God has given you, imperfect though it may be, when you begin to violate God’s Word. Which is why…

It must be shaped.

It must be heeded.

Shape Your Conscience

If our conscience is imprecise and fallible, we must calibrate it according to the precise and infallible Word of God. This means that there are times where we must subtract restrictions from our conscience: we feel that something is wrong, when really it is not (like eating meat, Rom 14:14). And there are times where we must add restrictions: we feel that something is permissible, when really it is not (like participating in pagan festivals, 1 Cor 10:14-22). Since none of us see ourselves entirely objectively, this shaping process must take place within the context of God’s people, the Church. See Andy Naselli’s helpful resource on this.

As you come to vote (or abstain from voting), you should seek to inform your conscience by God’s Word. You can do this through reading the Bible, receiving good teaching, and speaking with wiser Christians, and do all of this with a posture of humility. Further, you should also make sure you are well-informed about the candidates you are voting on. Do not rely on second-hand information or social media to paint an unbiased picture of either side.

You can read each candidates platforms (Trump and Harris). Admittedly, many of these are vague and unrealistic. Here is a helpful analysis of both Trump and Harris’ positions on major issues (as well as a popular, third-party platform for Evangelicals to consider, The American Solidarity Party).

Heed Your Conscience

But, no matter what, as you undertake this process, you must heed your conscience. There is no teaching in the Bible about how to vote in an election, nor that to vote in such an election means you endorse all of what the candidate stands for. But the Bible is abundantly clear that to violate your conscience is sinful (Rom 14:23). If your conscience will not permit you to vote for Trump, Harris, or either, then you must:

Investigate and interrogate that conviction with God’s Word and reliable information of the candidates. Just because you feel it, it doesn’t mean it is right. Ask yourself: Why do I believe that I cannot or must vote for this person? Is that conviction coming out of what the Bible clearly teaches? Does my view of the candidate correspond with reality?

Strive for an open mind. Most people form their views of a candidate off of snap decisions and hunches. Acknowledge your own prejudices and interrogate them with truth. Ask yourself: What is the most persuasive argument a sound Christian would make for the opposite decision I am making? Until you can answer that in such a way that doesn’t sound immediately foolish, you have not yet really tried to have an open mind.

If at all possible, ask a fellow church member who disagrees with you why they are voting the way they are. Do this to learn, not to change their mind.

If, after all that, your conscience remains bound, then heed your conscience.

The electoral college in America, however, does add a wrinkle to this. If I am a part of the minority political party in a state—a Democrat in South Dakota or a Republican in California—my vote is unlikely to change the outcome of the election since the state as a whole is highly unlikely to change. Thus, an individual who is not in a swing-state has a stronger argument for voting third-party (or not voting at all) and bearing no culpability in the outcome of the election.

Melania Trump’s decision to release an excerpt from her forthcoming book where she describes herself as a life-long, passionate defender of reproductive rights for women, further muddies the water.

Hang on, you might say, don’t individuals who refuse to vote or vote third-party do so precisely because they are unwilling to make compromises? True, but a compromise still takes place, if only tacitly. Even if you vote for a third-party candidate that you align with on every policy position perfectly—or you don’t vote at all—at the end of the day, one of the two major party candidates will be elected, and you will (however minutely) have played a small part in making that happen. Which means that you must accept the fact that by voting third-party (or not voting) you are making a compromise.