What Are Men For?

We castrate and bid the geldings be fruitful.

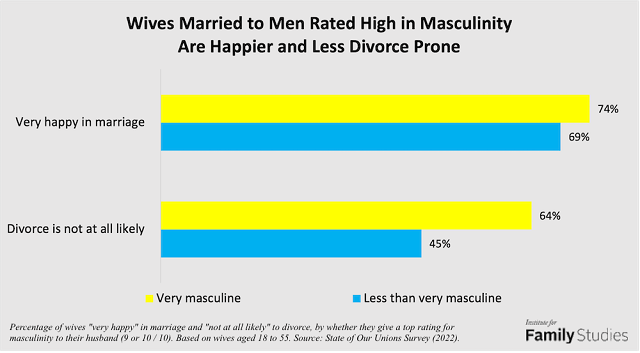

The masculinity conversation is strange. Somehow, it is a toxin that poisons young men, but also is a trait that most women (even liberal women) find attractive? Believe it or not, most women want men to be manly.

What gives?

The schizophrenic want it-hate it may be because the anti-masculine perspective is more performance than reality. But it may also be because there is no cohesive vision for what masculinity should be today. To twist a Keller-ism, Describe to me the masculinity that you reject, maybe I reject it too.

Here are a couple competing examples of what comes to mind when people talk about masculinity:

Machine-gun masculinity

Aesthetically, this masculinity wants to project the kind of leather-jacket ethos of the bad-boy: beards, pit-viper glasses, red-pill, fake balls hanging from the back of your truck, cigars, AR-15s. This is a muscular, don’t push me, ‘come and take it,’ kind of masculinity that defines manhood primarily in terms of strength, conquest, and a kind of emotional hardness. There is a kind of Nietzschean will-to-power here that isn’t embarrassed to assert itself, to demand respect, or fight. The world has been feminized and wants to control you. Men have become soft and need to rediscover the value of grit and resilience…mostly by creating montage videos of themselves working out, hustling (read: multi-level marketing schemes), and glaring at you with lockjaw-face behind their sunglasses.

Definitely not toxic masculinity

Happily deferential, unapologetically supportive of female empowerment, and overall just really, really nice guys. Gummy bear masculinity; Mr. Rogers masculinity; masculinity that has warning bells go off as soon as the word ‘masculinity’ is used. This is the perspective that feels uncomfortable pointing to any essential distinctions between men and women (except for when it serves to paint men in a negative light or women in a positive light). This is the man who exists to dismantle the power structures that his forefathers erected. Thus, he lives in a perpetual state of abnegation, defining himself by what he is not and atoning for whatever latent forms of toxic masculinity that indelibly reside within by calling it out wherever he sees it…in other men (of course). Cultivating a life of sensitivity, empathy, and listening are heralded as ideals, not to mention an abiding awareness of ways in which women are harmed by men in general, and traditional gender roles in particular.

Confused masculinity

Where most normal people reside. The two previous options feel so bonkers and speak in such dramatic tones that it leaves the average man unclear about what masculinity is. All they know is that extremely confident people online tell them that things that seem like basic human decency—like offering to help a woman carry a heavy package or telling your girlfriend that you love her—apparently proves that “you are the problem” with masculinity today. Either you are a beta-simp letting women control you with feelings and commitment, or you are perpetuating patriarchal heteronormativity that infantilizes women. Both perspectives are scathing and pharisaic in their rebukes, while missing what is correct in the other: strength and empathy are characteristics good men must have.

Most young men I meet feel confused about what it means to be a man and are anxious about misstepping either to the right or the left, especially when such missteps are tarred and feathered. So they hesitate, puppet the confidence of one side, retreat when it doesn’t correspond with reality, drift into ambiguity.

The dominant tone from the Big Voices™ over the past fifteen years have been predominantly negative towards men. In Peggy Orenstein’s book, Boys and Sex, she conducts interviews with teenagers and college students and asks them what they enjoy most about being a man. She says most drew a blank. “That’s interesting,” one college sophomore told her. “I never really thought about that. You hear a lot more about what is wrong with guys.”

This perpetual negativity has created a backlash, pushing young men towards the machine gun masculinity of men like Andrew Tate—a convicted sex trafficker and rapist who trains other young men on how to manipulate women into becoming prostitutes. Why would such a morally depraved man draw in so many? Simply because Tate is willing to say things like: it is good for men to be strong; men and women are different; discipline and ambition aren’t wrong. The fact that this is resonating so deeply tells us just how famished young men are for guidance, for someone to tell them that they are not the source of every problem in the world.

Both extremes—the muscular and apologetic forms of masculinity—contain elements of truth in them: men are strong in ways that are distinct from women and men have used that strength in selfish, destructive ways that have hurt many—especially women. But we need a better vision that encapsulates the good, while discarding the bad, that moves us beyond the shifty eyed confusion of uncertainty.

What Men Die For

In 1931, Helen Taft, the widow of the late president, William Howard Taft, unveiled a 13 ft. tall statue on the edge of the Potomac River in Washington DC. It was a monument to honor those who had died in the tragic sinking of the Titanic. More specifically, the monument was intended to honor the men who had died. The inscription on the front reads:

TO THE BRAVE MEN WHO PERISHED IN THE TITANIC

APRIL 15, 1912

THEY GAVE THEIR

LIVES THAT WOMEN

AND CHILDREN

MIGHT BE SAVED

ERECTED BY THE

WOMEN OF AMERICA

The boat’s architects didn’t plan well. There simply weren’t enough lifeboats to fit all of the passengers, and many drowned. In total, 50% of the children survived, 75% of the women, but only 20% of the men.

Why so few men?

In James Cameron’s 1997 blockbuster, The Titanic, when it comes time for people to board the lifeboats we see men panicking, shoving women and children aside, fighting for a spot on the precious few boats. British sailors draw handguns and fire into the air, crying, “Stand back! Stand back! Women and children first!” It is a terrifying scene of pandemonium, where civil virtues melt away and the fight for survival takes center stage.

But that never happened.

The universal testimony of the witnesses who survived the disaster is that the men voluntarily hung back and urged the women and children into the lifeboats.1

There were no guns drawn or men tossing women and children aside.

So why did James Cameron include that scene? Why twist history? A film reviewer for The New York Times asked, and answered, the same question: “If the producer and director had told the truth…no one would have believed them.” One author writes:

I have seldom read a more damning indictment of the development of Western culture…in the last century.2

At one point, Western culture had a clear enough idea of masculinity that men would bravely sink into the frigid Atlantic before they would let a woman or child do the same. Against both caricatures of today’s versions of masculinity, these men knew that the highest calling of a man, because he was essentially different than a woman, was: I will die so they may live.

One hundred years later, that kind of self-sacrifice was so implausible that filmmakers had to distort history to make their movies seem believable.

What Men Are For: Strength to Serve

When the apostle Paul exhorts the Corinthian church to “act like men,” he immediately follows it up with the command: “be strong,” (1 Cor 16:13).

Paul has in mind something more significant than the early church’s muscle mass—a strength of will and mind; a strength that curtails the dangerous impulses that reside within man. Yet, it is instructive that when he thinks of what it means to act like a man, strength immediately comes to mind.

On average men are physically stronger, heavier, and taller than women. This gives them not only a kind of power and stature that surpasses most women, but also an ability to endure more adverse circumstances.3

So, the question is: what is that for?

A man can use his strength to physically assault a woman, or place her in a lifeboat and try to brave the frigid water himself. Strength isn’t meant to exploit, but protect, provide. It is emblematic of a deeper spiritual reality that is more important than a man’s physical strength or height, but is nevertheless inherent to masculinity: to be a “man” is to be strong. To be a “good man” is to use one’s strength to sacrifice for the good of others.

Insisting on a male-protectiveness for women may sound infantilizing to women. Women could have been just as capable as men to bravely face an icy death, couldn't they?

Certainly.

But should they? Is it right for women to perish when men could take their place instead? In the spirit of egalitarianism, should the death rates of men and women on the Titanic been the same? If a man and woman are confronted by a criminal with a gun, what should happen: the man stands in front of the woman, or behind her? If you are a woman reading this: what would you want a partner to do?

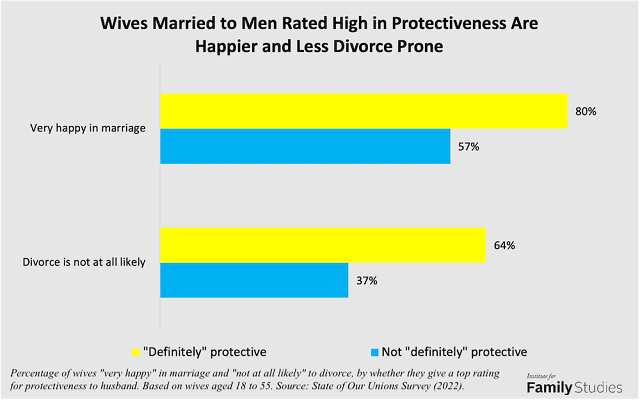

Against many progressive notions of equality, married women whose husbands are “protective” of them have higher rates of satisfaction in their marriage and are less likely to consider divorce.

Masculinity, strength, leadership—these are good things. But you cannot have these good things if you plug up the stream that they come from. If you insist that masculinity is inherently toxic and the only difference between men and women is how terrible men are, then you cannot—in the words of Lewis—make men without chests and expect virtue from them; cannot castrate and then bid the geldings to be fruitful.4

Men are strong in ways that women are not, and that is a bad thing only to the degree that men are bad.

The aim, then, shouldn’t be to erase the uniquely masculine aspects out of men or pretend they don’t exist, but instead should be aimed at transforming him into a virtuous man.

Here is where the old virtue of chivalry comes in. Chivalry is masculine strength for the purpose of service, especially for the protection of women. Léon Gautier, a French literary historian, consolidated his wide reading of the 12th and 13th century romances, into La Chevalerie (1884), a summary of what it meant to be a chivalrous man. One of his maxims reads: “Thou shalt respect all weaknesses, and shalt constitute thyself the defender of them.” Strength that protects, strength that serves.

Mary Harrington writes:

‘Chivalrous’ social codes that encourage male protectiveness toward women are routinely read from an egalitarian perspective as condescending and sexist. But…the cross-culturally well-documented greater male physical strength and propensity for violence makes such codes of chivalry overwhelmingly advantageous to women, and their abolition in the name of feminism is deeply unwise.5

Strength to serve, strength to sacrifice, strength to provide—these are good starting points for what it means to be a man.

Note: a small part of this article was adapted from another post from 2023.

“John Jacob Astor was there, at the time the richest man on earth, the Bill Gates of 1912. He dragged his wife to a boat, shoved her on, and stepped back. Someone urged him to get in, too. He refused: the boats are too few, and must be for the women and children first. He stepped back, and drowned.

The philanthropist Benjamin Guggenheim was present…when he perceived that it was unlikely he would survive, he told one of his servants, “Tell my wife that Benjamin Guggenheim knows his duty”—and he hung back, and drowned. There is not a single report of some rich man displacing women and children.” - D.A. Carson, Scandalous: The Cross and Resurrection of Jesus, p. 30-31

Scandalous: The Cross and Resurrection of Jesus, p. 30-31

Pay attention to my words “on average”—there are always outliers, but that doesn’t disprove the general rule.

From The Abolition of Man

Feminism Against Progress, cited in The Case Against the Sexual Revolution, p. 68-9

Very insightful essay.

I think men's strength has been reduced in recent decades to a sexual attraction. Muscles for men, like shapely figures for women.

I was puzzled recently when I saw a bunch of women online say they liked a guy's "before" gym picture better than his "after." They're performing this idea that men's strength is optional, that it's just to make women hot and bothered (or worse, to overpower them)--a vestige of an evolutionary advantage we've since outgrown.

But this isn't true. A man's strength is so much more than that. Since we disconnected it from chivalry, women wonder, "what for?" and then jump on the performative bandwagon of celebrating a reduction of men's strength as a virtue of equality.

I don’t understand how we asked men to stop raping and systemically abusing us and the response is “guess we won’t be chivalrous and kind anymore, can’t have anything around these parts!”