This article is part two of a series through Exodus 7:8-13. Read part one here.

As Moses is writing the Exodus narrative down, he is doing so with a certain purpose: a theological purpose.

Remember: Israel had been in the land of Egypt for 430 years before the Exodus event. That is long enough to have the culture of Egypt seep into the Hebrews. Further, when the Israelites leave, we are told that a “mixed multitude” go up with them (Ex 12:38). This most clearly refers to God-fearing Egyptians who have been converted by the signs and wonders performed in the ten plagues (Ex 9:20).1 Thus, though the people had left Egypt, they brought a lot of Egypt along with them.

As Moses leads Israel through the wilderness, he sees how much of their heart is strangely tethered to the land of slavery (cf. Ex 14:11-12; 15:24; 16:2; 17:3). So Moses deliberately crafts the narrative of Exodus in such a way that undermines the false gods of Egypt and exalts the power and supremacy of the one, true God: Yahweh. Throughout the story, Moses uses his knowledge of Egyptian religion and culture—which he would have been familiar with as he was raised in Pharaoh’s household (Ex 2:1-15; cf. Heb 11:23-28)—to take symbols associated with Egyptian religion, and ironically use them against Egyptian claims of superiority.

Of course, this is also Yahweh’s intent in His judgments on Egypt. At the last of the ten plagues, the Lord tells Moses: “…on all the gods of Egypt I will execute judgments: I am the LORD,” (Ex 12:12; cf. Num 33:4). Old Testament scholar and Egyptologist, John Currid and Kenneth Kitchen, argue that each of the ten plagues is aimed specifically at an Egyptian deity, demonstrating their futility and powerlessness to protect Egypt from Yahweh.2 God is not only judging the human entities of Egypt, but the dark, spiritual forces that stand behind them.

So, Moses, aware of God’s divine judgment on the gods of Egypt and wanting to help future generations not be tempted back to Egypt, crafts his story with a careful, deliberate eye towards undermining Egyptian religion.

This intentional theological craftsmanship is on full display in the battle of serpents in Exodus 7:8-13—a section so significant that Currid and Kitchen explain:

Exodus 7:8-13 is paradigmatic in that it defines for the reader the true issue at stake in the entire Exodus struggle…What the serpent contest portrays is a heavenly combat—a war between the God of the Hebrews and the deities of Egypt. For the biblical writer the episode was a matter of theology.3

Swallowing a Staff Isn’t a Party Trick

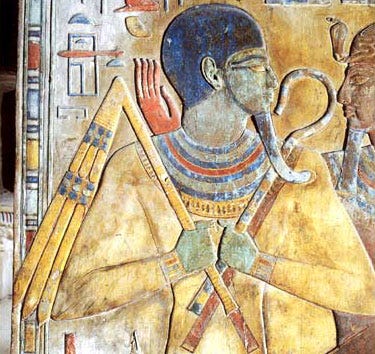

In the seemingly bizarre encounter between Moses/Aaron and Pharaoh/Magicians, we saw that the transformation of the staffs of Aaron and the magicians into serpents was not a randomly chosen party trick. In the previous article we saw that the Egyptians feared and loved snakes, believing them to be divine representatives of the Egyptian deities—Pharaoh himself wore a hooded crown intended to make him look like a serpent, since Pharaoh was believed to be divine himself. Also, the Egyptians believed that a shepherd’s staff was a symbol of kingship and authority.

The shepherd’s crook was the Egyptian hieroglyph for the Pharaoh, representing the Egyptian king’s guidance of Egypt, like a shepherd leading a flock. Significantly, Moses’ staff that is transformed and swallows the staffs of Pharaoh’s magicians is specifically identified as a shepherd’s staff in the Exodus story (Ex 3:1; 4:2). Yahweh is confronting Egypt’s religion by using its own symbol of divine authority: the staff of God.

Knowing the significance of staffs to Egyptians already gives us a sense of just how important it is that Aaron’s staff swallows the staffs of Pharaoh’s magicians. That obviously is a sign of the superiority of the God that Moses/Aaron are there to represent. But it is even more interesting than that. Egyptians believed that to “swallow” something had deep magical importance; to swallow something didn’t mean merely to destroy it, but to absorb its power, authority, and knowledge.4 Thus, for Yahweh’s staff to swallow the magician’s staffs would have communicated something terribly foreboding to the watching Egyptians.5

Even more alarming for the perceptive Egyptian (or Egyptian-ized Hebrew), the Hebrew word for “swallow” (bala, בָּלַע) is only used one other time in the entire book of Exodus: to describe Pharaoh and his armies being swallowed in the Red Sea, “You stretched out your right hand; the earth swallowed (בָּלַע) them,” (Ex 15:12). Thus, Yahweh’s “swallowing” of Egypt’s magical rods served as an ominous sign of an even more dramatic “swallowing” to come: the swallowing of not only Egypt’s armies, but of Pharaoh himself: the human representative of Egypt’s gods.

This dramatic event would have been interpreted to other Egyptians as the Hebrew God’s total and utter domination of Egyptian deities.

A Dragon-Gulping Dragon

In the next article, I will examine the specific word that Moses chooses to describe precisely what the staffs transformed into: dragons (tahneen, תַּנִּין). Not only is this an arresting image for modern readers—a battle of dragons took place in Pharaoh’s court?—but it would have carried even more significance to the ancient reader.

A Dragon-Gulping Dragon

You remember that one time that Val Kilmer got into a magic-fight with Steve Martin and Martin Short?

See also Lev 24:10-11, where Egyptians are present in the assembly of Israel as they wander in the wilderness.

See John D. Currid and Kenneth Kitchen, Ancient Egypt and the Old Testament (Grand Rapids, Mich: Baker Academic, 1997), 113-18 for a detailed list of the different Egyptian deities each plague was directed towards.

Currid and Kitchen, 86.

John Currid, Against the Gods, 129.

This also makes Pharaoh’s hard-heartedness even more pronounced, since he would have been aware of the significance of Yahweh’s staff swallowing the magicians.