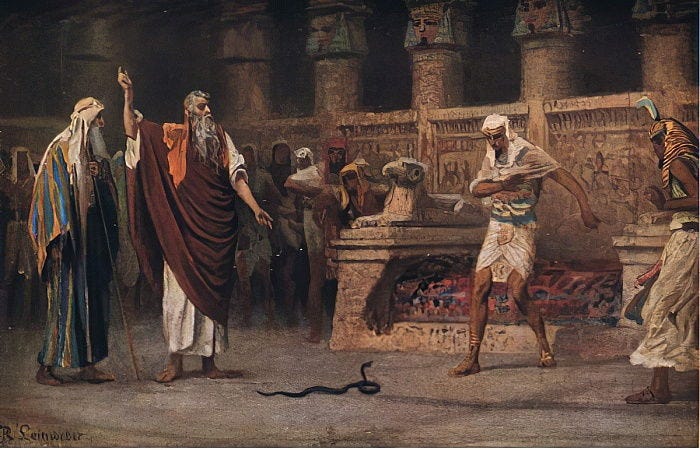

The Exodus represents the archetypical act of Israel’s deliverance in the Old Testament. It is through the triumph of Yahweh over the powers of Egypt (represented by Pharaoh) that all future generations would see and remember the mighty right hand of Yahweh working salvation for their people (Ex 15). However, prior to the fantastic signs and wonders worked at the Reed Sea, before the Passover, and before any of the plagues devastated the land, there is an interesting interaction between Yahweh and Pharaoh. Pharaoh, unaware that his kingdom is teetering on the brink of destruction, enters into a duel of sorts with Moses and Aaron. Both Aaron and the magicians of Pharaoh throw down their staffs and they immediately turn into serpents, but Aaron’s staff/serpent then devours the magicians’ staffs/serpents. Despite this miraculous encounter, Pharaoh’s heart is hardened and the ten plagues commence. How should one interpret this story? It appears to be straightforward enough, falling in line with the other spectacular acts of judgment throughout the Exodus narrative. However, there are a few features that make this story unique.

In a series of articles I will argue that the main point of the confrontation is the demonstration of Yahweh’s superiority over the gods of Egypt through the superiority of Aaron’s staff over the magicians’ staffs. This display of Yahweh’s superiority and strength will serve as a portent of the rest of the acts of judgment against Pharaoh. This will be demonstrated by a close examination of the word used to describe the transformation of Aaron’s staff, תַּנִּין (pro. tahneen), both in the Bible and in comparative ancient Near Eastern literature.

Exodus 7:8-13

After Moses and Aaron initially fail to secure the respite that Israel was hoping for (Ex 5), Yahweh commands them to return again to Pharaoh (7:2), but this time he tells them to be prepared to prove themselves by working a miracle (7:9). When Yahweh initially called Moses, he was given three different signs to validate his authenticity as a spokesmen for Yahweh: a staff turning into a serpent and back into a staff, leprosy appearing and disappearing suddenly, and water from the Nile turning into blood once poured onto dry ground—each sign being practiced only if the previous sign did not produce belief in the audience (4:1-9; cf. 4:21). However, here Yahweh only commands the first sign to be practiced: the staff becoming a serpent (7:9). Moses and Aaron dutifully obey, and Aaron casts down his staff before, “Pharaoh and his servants, and it became a serpent,” (7:10). Immediately, Pharaoh summons his, “wise men and the sorcerers and…the magicians of Egypt,” (7:11) and they are able to replicate this miracle by their “secret arts.” But, shockingly, Aaron’s staff proceeds to devour all of theirs (7:12). Pharaoh, nonetheless, is unmoved, precisely as Yahweh had said (7:13; cf. 7:1-5). The fact that the next plague is the Nile turning into blood (7:14-25)—mirroring the third and final sign given to Moses back in 4:9—may be a subtle indication of the depth of Pharaoh’s unbelief; the intermediate sign of leprosy was unnecessary due to the hardness of Pharaoh’s heart.

The Staff of God

The Exodus narrative places an unusual focus on the staff that Moses and Aaron use. When Moses is commissioned by Yahweh, the first miraculous sign given to him is the transmogrification of his staff into a serpent (4:1-4). However, the staff appears to be intended for more than just this one sign, for as Moses leaves the burning bush, Yahweh reminds him to, “take in your hand this staff, with which you shall do the signs,” (4:17, note the plural: signs). Even more surprising, in 4:20 Moses’ staff not only is given a divine significance (“staff of God”), it is labeled alongside his family as he returns to Egypt, “So Moses took his wife and his sons and had them ride on a donkey, and went back to the land of Egypt. And Moses took the staff of God in his hand,” (cf. 17:9). The staff is then used repeatedly throughout the plagues (7:15, 17, 19-20; 8:5; 8:16-17; 9:23; 10:13; cf. 17:5) and climactically at the parting of the Reed Sea (14:16). Of the 63 appearances of this word for “staff” in the Hebrew Bible, over half appear describing Israel’s relationship with the Pharaoh’s.1

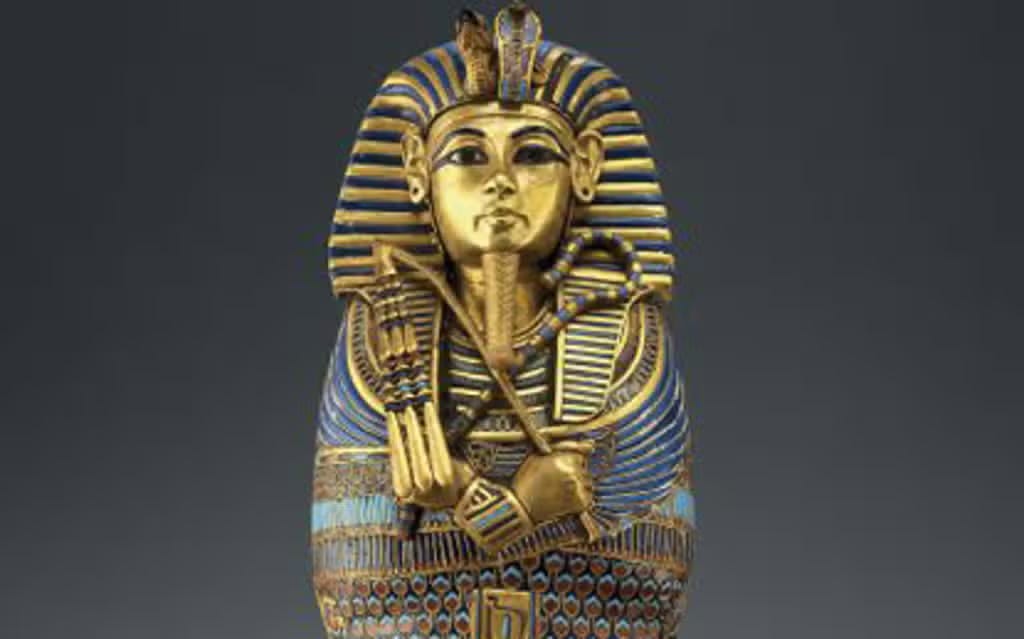

John Currid has delved deeply into the specific Hebrew term for staff (מַטֶּה), and its Egyptian etymology (originally from mdw).2 While certain Egyptian words for “staff” were used exclusively for deities and royalties (hket, nhhw) the mdw, “was the simple ordinary tool of everyday fieldwork; in fact, a variation of mdw was used in ancient Egypt to identify the guard or attendant of herds of cattle (mdw ke-hd).”3 Thus, the identification of Moses’ staff in Exodus 4:2 as the staff he was using while tending his father-in-law’s flock (3:1) would identify his staff as a mdw. But while mdw could refer to a humble walking-stick or shepherd’s crook, the term also began to take on cultic and royal overtones in Egyptian culture. The idea of a “holy staff” (mdw spsy), a staff held by priests to represent the deities, and the “rod of God” (mdw ntr), a staff held by the Pharaoh to represent his divine authority and power, was popular from 1550-1070 BC.4 Sarcophagi, hieroglyphics, and statues featuring Pharaohs and priests wielding rods/staffs abound. Magicians in Egypt likewise carried staffs, believed to be endowed with magical powers from the gods. Archaeology has even uncovered documentation of, “scenes of magicians holding rods in their hands that could instantly be turned into snakes.”5

The emphasis on Moses’ staff in the Exodus account now becomes clearer—and why it receives a divine appellation, “the staff of God,” (4:20). It appears that Yahweh is employing dramatic irony in his confrontation with deities of Egypt, represented by Pharaoh and his magicians. Yahweh takes Egypt’s own symbol of authority, power, and divinity (the staff) and turns it on its head, using it to confront their religious claims of superiority.

Even the transformation of the staff into a snake itself appears to fall in line with this divine mockery. The Egyptians both loved and feared snakes, and often associated them with the gods. Pharaoh’s very crown, similarly believed to possess and represent the power of the gods, was a dilated hood (meant to represent a cobra) with twin snakes wrapped around, facing forward. The serpent goddess, Wadjet, and the vulture-goddess, Nekhbet, manifested their power and sovereignty in the front of the king’s crown where a figure of an enraged cobra sat.6 Sometimes, Pharaoh’s staff itself took a serpentine form.7 That a Hebrew (the slaves of Egypt) representing a God Pharaoh had never heard of, would present itself in the very form the Egyptians loved and feared so much—only to devour the staffs/serpents of the magicians—would have been a severe blow to Pharaoh’s pride and apparent divine rule. It was, in sum, a means of divine mockery—taking the gods of Egypt head on and beating them at their own game.

This is why in the confrontation with the magicians in Exodus 7:8-13, rather than saying that Aaron’s snake devoured the magicians’ snakes, the text states that Aaron’s staff devoured the magicians’ staffs: “For each man cast down his staff, and they became serpents. But Aaron’s staff swallowed up their staffs,” (Ex 7:12).

The author is conveying that the God of Moses and Aaron is superior to the gods of Egypt; Yahweh alone possess ultimate sovereignty.

Purging Egypt out of Israel

This article is part two of a series through Exodus 7:8-13. Read part one here.

This article is adapted from a longer paper. You can read the whole thing here.

John D. Currid, Against the Gods: The Polemical Theology of the Old Testament (Wheaton: Crossway, 2013), 112.

Currid, 112.

Currid, 112-13.

Currid, 113-15.

Currid, 115-16.

John D. Currid and Kenneth Kitchen, Ancient Egypt and the Old Testament (Grand Rapids, Mich: Baker Academic, 1997), 87-92.

Karen Randolph Joines, Serpent Symbolism in the Old Testament: A Linguistic, Archaeological, and Literary Study (Haddonfield, N.J: Haddonfield House, 1974), 85.

This is a fascinating article & also your writing on the dragon and the staff in the same scene of Exodus. Dragons always make me think of those Studio Ghibli animations where the rivers are synonymous with these long etherial dragons - like in Spirited Away. Have you thought about how this event in Exodus could relate to 2 Timothy 3 - Now as Jannes and Jambres withstood Moses, so do these also resist the truth... - this part of Timothy relates to the Last Days?