This article is part of a series on the contest between Moses/Aaron and Pharaoh and his court magicians in Exodus 7:8-13. Read part one, part two, and part three.

As Moses is recording the showdown between himself1 and the magicians of Pharaoh’s court in Exodus 7:8-13, he tells us that Aaron’s staff and the staffs of the magicians turn into tahneen (תַּנִּין2)—a word that is used to describe dragons/sea-monsters in the rest of the Old Testament.

Since Pharaoh is entirely unmoved by the encounter, we can assume that Moses is using some hyperbolic language to describe the staffs transforming into dragons.

But, that naturally leads us to consider: Why did Moses use that word here?

The Chaos Monster

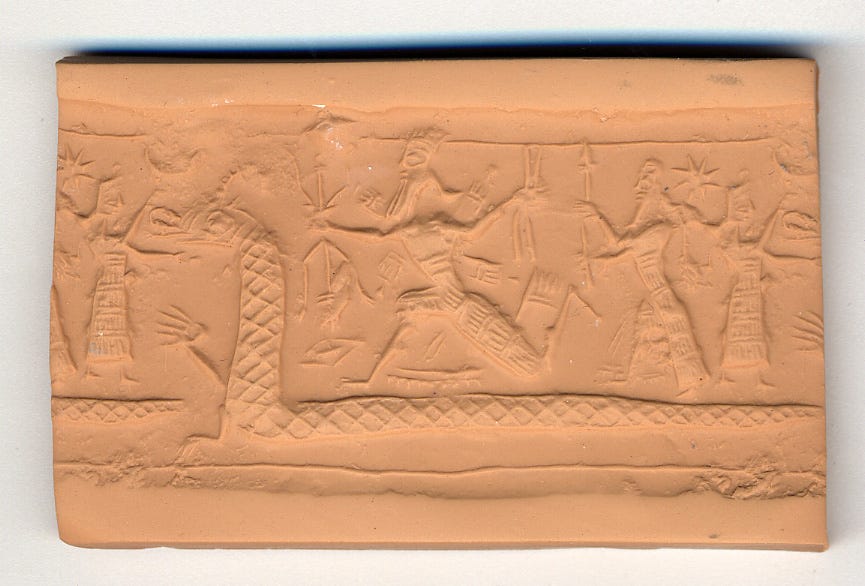

The theme of gods bringing order out of chaos through conquering the primordial sea, or a sea-monster (representatives of chaos) is a common one in the ancient world.3

For instance, in Mesopotamian myths, such as the Enuma Elish, Marduk, king of the gods, slays the primordial chaos monster, Tiamat, the goddess of the sea. Marduk then uses her slain body to create the cosmos.

In Egyptian cosmogonies, the god Re entered into the world out of the primordial waters (Nun) through self-creation and brought order out of chaos by seizing control from the eight other chaotic gods.4 Every day, as the sun-god made his journey across the sky and into the underworld, he had to battle the evil serpent Apopis, “the demon of chaos…who represented all that was outside the ordered cosmos.”

In Ugaritic mythologies, the rebellious sea-god, Yam,5 is defeated by the storm-god Baal, and through this victory is then enthroned as king of the gods.

Many more mythologies could be recounted,6 but throughout the ancient world we find a common theme employed: the god(s) must fight against the forces of chaos (usually represented by water/dragons) to create peace and equilibrium in the world and in their kingdom.

The author’s of the Bible were aware of these popular mythologies and images and employ them throughout the narrative through references to Leviathan, Rahab, and the tahneen.

The Tahneen

The Hebrew word tahneen comes from an Ugaritic word tunnanu. In the Ugaritic Baal-cycle, the tunnanu is a mythical sea-dragon defeated by the storm-god, Baal.7 Elsewhere in Ugaritic mythology, the tunnanu is called Leviathan (ltn), whom possesses seven heads (cf. Ps 74:14; Rev 12:3), and is called not only the ‘twisting serpent’ (cf. Job 26:13; Isa 27:1) but also the ‘crooked serpent’ (cf. Isa 27:1).8

Just to make it painfully clear that the Biblical authors are intentionally evoking this mythology—and in case you aren’t looking up all these Scripture references in the parentheses—read Isaiah 27:1,

In that day the LORD…will punish Leviathan the fleeing serpent, Leviathan the twisting serpent, and he will slay the dragon that is in the sea.

In the Bible, the tahneen is parallel with Leviathan (Isa 27:1; Ps 74:13-14) and Rahab (Isa 51:9). This is interesting because Leviathan and tunnanu have been found in Ugaritic works (Canaanite), while rahab comes from Mesopotamian (Babylonian) mythology.9 Rahab, of Akkadian origins, originally was an expression referring to the surging of water, but began to be associated with Tiamat, the chaotic goddess of the sea against whom Marduk battles.10

The fact that these three terms—which can be found in differing ancient near-eastern traditions—are used repeatedly in parallel structure with one another (Isa 27:1, 51:9-10; Job 26:12-13; Ps 74:13-14) likely proves that these various mythological creatures have been combined into one figure in the Hebrew Bible: The Tahneen.

For our purposes regarding the Exodus story, the Egyptian and Canaanite symbolism and religious worldview are of particular importance.

Ugaritic Symbols

In the Baal-cycle, the sea-dragon tunnanu is associated with the rebellious sea-god, Yam, whom Baal defeats alongside the tunnanu and is enthroned as king.11

Interestingly, the location that Yahweh commands Israel to march towards just before the Re(e)d Sea and the location Pharaoh’s pursuing armies encamp at is described as “in front/before the face of Baal-zephon,” (Ex 14:2, 9).12

Baal-zephon appears to be an unknown location near the Re(e)d Sea (cf. Num 33:7). However, in Ugaritic mythology, Baal-zephon is the abode of the divine council and the location of Baal’s palace.13 Thus, one could interpret Yahweh’s victory over the Re(e)d Sea as taking place on Baal and his council’s front door, demonstrating that it is Yahweh, not Baal, who is the true conqueror of Yam (Hebrew for “sea”; yam, יָם). Therefore, the Bible appears to be intentionally employing the ancient pagan mythological concepts of the chaotic waters and sea-monsters to depict the entropic and wicked forces that Yahweh has and will conquer.14

Egyptian Symbols

We have already explored many other Egyptian symbols employed in the Exodus narrative, including staffs and serpents, but it is worth reflecting on the role of order out of chaos in Egyptian mythology. As noted above, the sun god Re emerges out of the primeval chaos waters of the god Nun through self-creation, and then is responsible for maintaining order.

This Egyptian concept of order that is established out of the conquering of chaos was called ma’at; George Posener defines ma’at as, “the equilibrium of the whole universe, the harmonious co-existence of its elements, and the essential cohesion, indispensable for maintaining the created forms.”15

The self-stylized god of Egypt, Pharaoh, was responsible for ensuring that ma’at reigned in Egypt. Currid explains:

In ancient Egypt, the king had the duty to maintain ma’at; he was considered the personification of universal order…The importance of ma’at for Egyptian kingship should not be underestimated. The idea of ma’at played a central role in the king’s identification with the god Horus…Restoring and maintaining this harmony were imperatives for the Egyptian king, expectations that befit his office as the son of Re and the god-king.16

Maintaining order through mastering the forces of chaos—represented by the chaotic waters and serpentine monster—this is the responsibility of Pharaoh, the embodiment of the supreme Egyptian deity.

The Deep

Added to this, tahneen often stands in parallel with the Hebrew word te’hōm (תְּהוֹם), the subterranean primeval waters of “the deep” that represent chaos, darkness, and disorder, an idea ubiquitous in ancient Near Eastern cosmogonies.17 The te’hōm is the dwelling place of Rahab, the tahneen in Isa 51:9-10 and of Leviathan in Job 41:32.

Some of the first words of Genesis evoke these images of disorder and chaos: “The earth was without form and void, and darkness was over the face of the deep (te’hōm).” The Spirit broods over these dark waters like a mother bird, bringing warmth, light, and order (Gen 1:2ff). Later, when God wants to de-create the world through the great flood, he opens up the great fountains of the te’hōm— that is, He unleashes the forces of chaos (Gen 7:11). This is why Noah’s exit from the ark is stylized in the narrative as a recapitulation of the Genesis one story: God’s breath/Spirit blows over the waters and the fountains of the te’hōm are closed (Gen 8:1-2).18

Yet, the tahneen and the te’hōm aren’t abolished—they are subdued and will wind up serving God’s purposes, bringing Him glory and honor:

“Praise the LORD from the earth, you great tahneen and all te’hōm” (Ps 148:7).

The only reference to the te’hōm in the Exodus story, significantly, is in the song of Moses. There the te’hōm both serve as the instrument through which God vanquishes Pharaoh, and is a force that is itself conquered:

Pharaoh’s chariots and his host he cast into the sea,

and his chosen officers were sunk in the Red Sea.

The te’hōm covered them;

they went down into the depths like a stone.

- Ex 15:4-5At the blast of your nostrils the waters piled up;

the floods stood up in a heap;

the te’hōm congealed in the heart of the sea.

- Ex 15:8

What’s the theological significance of this? Reminiscent of Genesis one and eight, God’s Spirit/breath alone can have mastery over the forces of chaos. When human beings (like Pharaoh) try to, they are utterly destroyed.

This theme will return as we examine the battle of the tahneens in Exodus 7:8-13.

Polemical Theology in Exodus

As I have already argued, as the Spirit as bearing Moses along in the crafting the narrative of the Exodus story, He is doing so with a polemical edge. He is trying to deliberately undermine the competing religious worldviews that have indoctrinated the Hebrews as they wander through the desert.

Now, fully furnished with an understanding of the significance of the staff of Moses, the hermeneutical significance of Ex 7:8-13, the translation of tahneen as “dragon” and its mythological connotation of chaos/chaotic waters, we are prepared to return to the text and see what new exegetical insights can be gleaned.

The Dragon Slayer

This is the final installment in a series of articles on the episode of Moses/Aaron confronting Pharaoh/the magicians in the duel of serpents/staffs in Exodus 7:8-13. Here are the preceding articles:

And Aaron

Usually transliterated as tannin, but to come close to the Hebrew pronunciation, I’ve chosen to transliterate it as tahneen.

Othmar Keel, Symbolism of the Biblical World: Ancient Near Eastern Iconography and the Book of Psalms, trans. Timothy J. Hallett (Winona Lake, Ind: Eisenbrauns, 1997), 47-56.

Currid and Kitchen, Ancient Egypt and the Old Testament, 36.

The Hebrew word for “sea” is also yam, יָם

In Hesiod’s Theogony, the hundred-headed serpent monster, Typhon, fights with Zeus for control of the gods upon a beach (where land and water meet) and is ultimately conquered. Through this victory, Zeus becomes the supreme ruler of all other gods.

In Norse mythology, the massive sea-serpent, Jörmungandr, (the son of Loki) battles with Thor at Ragnarök.

In Vedic mythology, the storm god Indra slays the dragon Vritra—the monster responsible for drought.

Botterweck, Ringgren, and Fabry, Theological Dictionary of the Old Testament, Vol 15, 727.

Day, 4-5; Joines, Serpent Symbolism in the Old Testament, 9.

Botterweck, Ringgren, and Fabry, Theological Dictionary of the Old Testament, Vol 15, 729.

G. Johannes Botterweck, Helmer Ringgren, and Heinz-Josef Fabry, Theological Dictionary of the Old Testament, Vol. 13, Annotated edition edition (Grand Rapids, Mich: Eerdmans, 2004), 354-55.

Day, God’s Conflict with the Dragon and the Sea, 4.

לִפְנֵי֙ בַּ֣עַל צְפֹ֔ן

Katharine Doob Sakenfeld, ed., New Interpreter’s Dictionary of the Bible Volume 1: A-C (Nashville, TN: Abingdon Press, 2006), 374.

Sakenfeld, 368.

Cited in Currid and Kitchen, Ancient Egypt and the Old Testament, 118-119.

Currid and Kitchen, Ancient Egypt and the Old Testament, 118.

Botterweck, Ringgren, and Fabry, 575-78. While the Babylonian sea goddess’ name, Tiamat, is not the source of the Hebrew word tehōm, the words appear to be lexically related.

More connections between Genesis 1 and 8: the waters are separated from the dry land (Gen 1:9; 8:3); the ark lands on a mountain, Eden is a mountain (Ezek 28:13-14; Gen 8:4); the dove sent from the ark (Gen 1:2; 8:11); seven days (Gen 8:10-12); animals roam the earth (Gen 1:24; 8:17); “be fruitful and multiply” (Gen 1:22, 28; 8:17). Moreover, like Adam, as soon as Noah emerges into this new creation, he is immediately tested in a garden by a fruit—and like Adam, fails (Gen 9:20-28).